Written by Jenifer Chrisman on September 2, 2021.

“When the handler went to sleep, he slept with the palm of his hand under the throat of Lucky. Lucky had been taught never to bark or growl, but if he sensed anything out of the ordinary at night, his throat would vibrate in a silent growl, which would awaken the handler, who would then rouse the other Marines.”

– Donald R. Walton

From house pet to “war dog” to war vet, 18-month-old Lucky, a German shepherd, was the second one in his family to join the war effort. A service members most trusted companion, dogs such as Lucky also were known as “Red Cross dogs,” “devil dogs” and “scout dogs.”

Donald R. Walton, Lucky’s owner, had enlisted in the Navy and was preparing to depart. His wife and young son were moving to Washington D.C. from Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, but couldn’t bring Lucky with them. After seeing a publicized need for Dogs for Defense, they enlisted Lucky into the U.S. Marine Corps.

Lucky, loaded in a crate bearing the label “USMC Devil Dog,” was boarded on a train and sent to Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, North Carolina, for basic training under the command of (veterinary doctor) Captain William W. Putney. Unlike training during World War I, dog training during the second World War was much more humane. A memo, circulated in 1943 to those training dogs, stated, “Under no circumstances will physical punishment or abuse be tolerated.” During WWI, the training manual recommended the use of a spiked “gag” collar and a whip, as well as stepping on the dog’s paw if the trainer was wearing soft-soled shoes.

Training for dogs like Lucky (reward, not punishment based) and his handler (who is unnamed) was to make them one unit. Every test and exercise were taken together. The dogs were taught to follow their handlers’ orders without hesitation. And, because of the need for silence in the field to avoid detection, they learned to decipher hand signals and near inaudible whistles. It also was the handlers’ responsibility to care for and feed the dogs. All of this created an unbreakable bond that could only be severed by one or both of their deaths or by the end of their enlistment, as it was the established protocol of the USMC to give the family who enlisted each dog first choice of taking the dog back after discharge.

Granted the rank of Private First Class (a higher rank than the handler to discourage abuse) after completing basic, Lucky and his handler were shipped out to Guam and other islands in the Pacific in 1945. His sole job was to root out Japanese soldiers who were hiding out in elaborate networks of tunnels and caves as the Allies secured the islands.

Lucky and his handler, like all the Marines in their unit, slept in foxholes dug out wherever they stopped. According to Walton, after only a few expeditions with Lucky, the holes were dug for them by the other Marines because of their high regard, as well as always wanting Lucky close to hand.

Lucky’s handler quickly started sleeping with his hand under the shepherd’s throat. Trained to make no audible sounds, Lucky’s throat would vibrate with a silent growl if he sensed a threat during the night. This would in turn wake his handler who would then wake the unit if needed.

When the war ended, Lucky and his handler were sent to Japan. There they became part of the occupation forces patrolling during the Japanese transition to re-form a civilian government.

Lucky, along with other dogs of WWII, received detraining, created by Putney. Because both their training and their duties during the war required round-the-clock hyper alertness, as well as attacking if needed, detraining used supervised reentry into civilian life. This allowed the dogs to be carefully socialized with people of all ages and types. They also were sent home with instructions for the families, which included healthy outlets (exercise and play requirements) for their energy and command words that should never be used to keep the dogs from attacking.

According to Putney, out of the 549 dogs he and his men trained during WWII, only four were euthanized because they could not be rehabilitated. Despite proof detraining could be and was successful, during the Korean and Vietnam conflicts, dogs were euthanized and disposed of at the end of their service. Putney lobbied Congress and the President, and in the late 1990s successfully ended this practice.

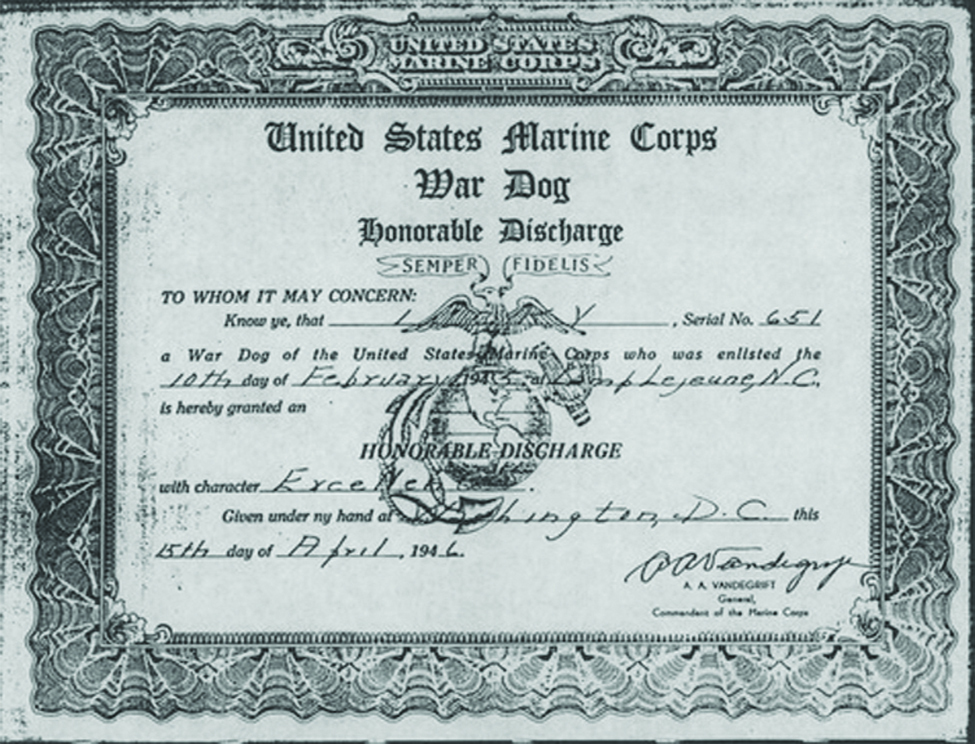

From completion of basic training until he was discharged, the Waltons were kept apprised of Lucky’s progress. However, even though Lucky was assigned a serial number (651) and the Waltons were given a San Francisco Army Post Office number to write Lucky via his handler, they never did. According to Walton, “We were still having to move around a lot and everything was uncertain. We thought since we had actually given away the dog that perhaps it wasn’t a good idea to keep up correspondence.”

After detraining, Lucky was honorably discharged. And although the handler implored the family, on several occasions via letter, to let him keep his beloved companion, the Walton family wanted Lucky back. Walton explained it was like any service member returning home after his service ended. But he did admit it was the most difficult letter he ever had to write.

Lucky was reintroduced to the Waltons at the train station near their new home in Richmond, Virginia, in April of 1946. Lucky immediately recognized Walton, as well as his wife and older son. But their new home was unfamiliar. He slowly and carefully searched the entire house before returning to Walton and laying down at his feet.

Although he loved his family and considered himself their guardian, Lucky never stopped missing his handler. According to Walton, “Whenever he saw anyone in uniform, he wanted to go up and see who it was. He was hoping that someday he would meet his handler again.”

Retired PFC Lucky passed in 1953 at the age of 14. The only physical reminder is his Honorable Discharge certificate, which can be located in the Library of Congress, American Folklife Center, Veterans and History Project.

Sources:

· https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2015/04/faithful-and-true-even-to-death/

· https://americacomesalive.com/wwii-war-dog-lucky-the-family-pet

· https://www.bookreporter.com/authors/captain-william-w-putney

· https://bornforpets.com/2021/06/29/do-military-dogs-get-paid/