Written by Molly Swift on November 7, 2013.

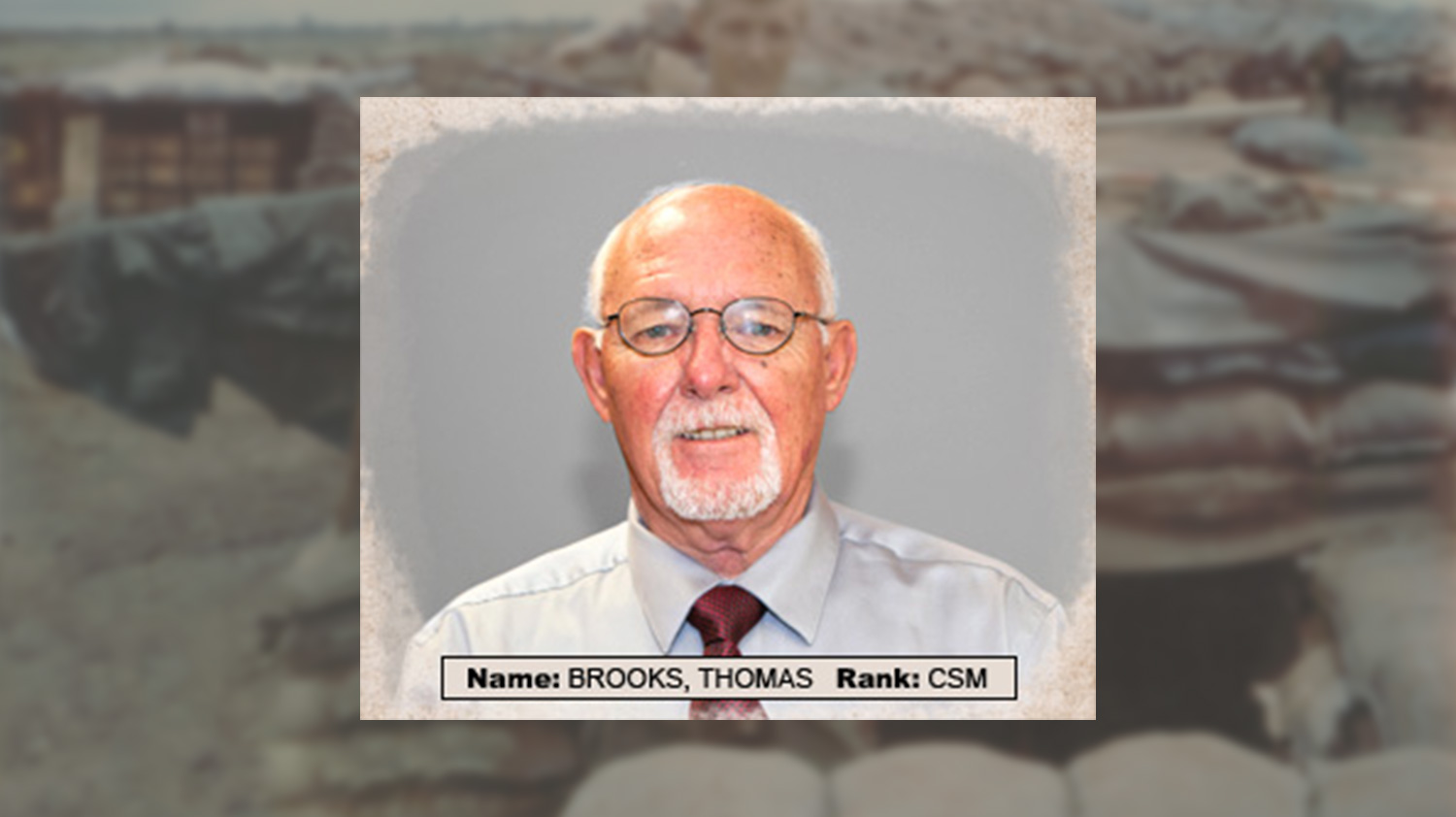

What does a native of Mississippi do when faced with a challenge? Rise to the top, of course! That’s just what Command Sergeant Major (retired) Thomas R. Brooks—born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi—did after he enlisted in the Army in August 1967.

One of six sons, Thomas Brooks was the only one of the brothers to make a career of the Army. It was the sixties; after graduating from high school, young men knew what was likely in store for them: “We would take a pre-induction written test and a physical when we reached the age of 18, then just wait for our number to be called for the draft. During the late 1960s, thousands were being drafted every month.”

Some readers may be unfamiliar with conscription – the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service – but for a long time the system was in place as a way to fill vacancies in the forces which could not be filled on a voluntary basis. President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, which created the country’s first draft and established the Selective Service System as an independent Federal agency. The draft was in place from 1948 until 1973, in peacetime and during periods of conflict.

The Draft and Vietnam

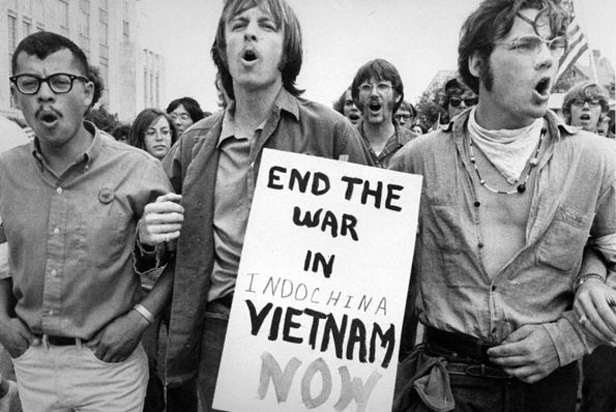

The sixties have been repeatedly described as a time of great civil upheaval, conflict and socio-economic change. Tensions were high as a result of gender and racial inequality, segregation, polarizing poverty and a development of many counter-cultures striving for recognition and validation. Subsequently, during the mid-late sixties, despite a healthy sign-up rate from citizens, the Army needed to rely on the draft to man the conflict in Vietnam. As a result, Tom’s “career” was initially a case of going where he was needed, “These were times when a warm body was what the Army needed and the Army put you in the job where you were needed most.”

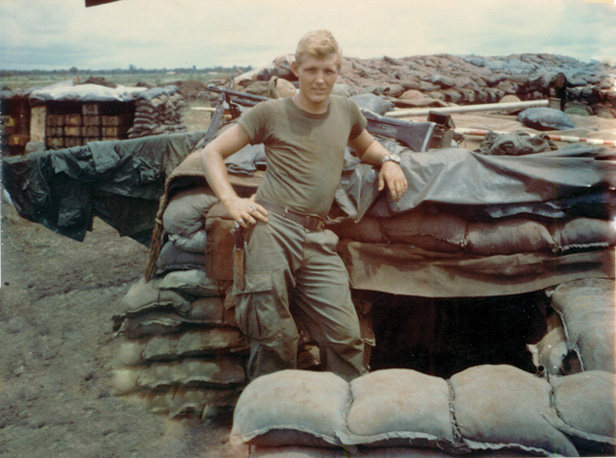

Two days after Christmas 1967, Brooks was off to Vietnam. “I remember walking down a boardwalk at Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam—there were no sidewalks, just boardwalks that were built due to the mud during the rainy season. I remember saying “364 more days." That seemed a lifetime.” He was assigned with the 4th Infantry Division at Pleiku Province in the central highlands of Vietnam. The first five months he was assigned to the base camp battery comprising of six howitzers, but then according to Brooks, in May 1968, “all hell broke loose.” The battery he was assigned to took some heavy hits—20 to 30 people were either killed or wounded—and all remaining battery personnel were immediately transported to Landing Zone (LZ) Brillo Pad. Despite the small area, the LZ was constantly busy; fire missions were performed 24-hours a day, round the clock – someone was always on shift and ready to shoot.

Brooks was promoted to Corporal (E4) in June and to Sergeant (E5) in August; it was where he wanted to be – “no more KP!” He was also a section chief – his gun was the base piece and that section always moved first, with the advance party to fire registration rounds. It was his first introduction to leadership and the art of influencing, “It took much teamwork and respect to survive in Vietnam. I think my gun section was just about the best group of guys in the world.”

At his next promotion board, Brooks was asked if he was going to stay in the Army; he responded he didn’t know much about the Army since he had only been to basic training, AIT and Vietnam. “I did not know anything about the Army except it gave me the opportunity to live like an animal and develop an affectionate relationship with a D-handle shovel.” Not giving it any further thought, Brooks returned to his duties and looked forward to the return home, now less than 90 days away.

When the time came for Sergeant Brooks to return to the United States, he discovered the benefits to doing a first-class job. The board had recommended Brooks for promotion to Staff Sergeant (E6); “Who would have thought I came to Vietnam a slick-sleeve Private and would return home one year later as a Staff Sergeant? It paid to do a good job. I was amazed and honored.”

Home and the Future of the Real Army

After a short leave, SSG Brooks moved onto his assignment in Fort Carson, Colorado. He had approximately 18 months left of his enlistment and wasn’t considering making the Army his career, although he was looking forward to learning about the “real Army” following his experience in Vietnam. Assigned to C Battery, 2nd Battalion, 130th Field Artillery, Brooks found the Fort Carson assignment only yielded more culture shock.

“The unit was part of the Lawrence, Kansas National Guard. All these guardsmen knew one another back in Kansas – most were farmers by trade and seemed to do their Army job in a good ol’ boy fashion. The bunk beds were in the front and the wall lockers were in the rear of the building – the interesting thing about the wall lockers was the only thing they contained was empty beer cans.”

Tom Brooks saw his expiration term of service (ETS) come around on August 10, 1970. He took a civilian job as control clerk with a data processing company in Jackson, Mississippi and though the people were good people (the pay wasn’t so great), something was missing. Brooks missed the camaraderie he’d found in the Army. So, on his way to work on evening Brooks stopped by the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station and reenlisted. The Brooks family packed up and moved back to Fort Carson.

It wasn’t until a year or more after Brooks reenlisted that he was introduced to recruitment as a career option. Speaking to his Chief of Firing Battery (Platoon Sergeant), Brooks realized the Army was facing a time of transition: “When I decided recruiting might be a challenging endeavor, it was because I saw change as being a good thing. The Army had been in a deep rut since WWII. A conscripted Army required minimal skill among the leaders who really didn't have to lead. During the peak of the draft the Army had "shake and bake" schools to train soldiers to be NCOs. A lot of the officers were selected to go to OCS at the reception station based on their education. There was no boarding and screening process. Ending the draft forced emphasis on leadership development, case in point, NCOES started in the early 1970s, as did Command and Staff College and the War College.”

The late sixties had taken its toll on the public’s perception of the Armed Forces; the draft, the assassinations, the anti-war movement and public riots simply meant people were disgusted with the way things were going in the United States. The Army had adopted a Volunteer Army (VOLAR) concept which entailed big pay raises, increased funding for units, and the push to recruit was under way. Brooks and his boss completed the application and drove 60 miles north to Denver to apply for recruiting duty.